After a century or more in business, these companies know a thing or two about how to stand the test of time. Here, they share the secrets to their longevity.

The year 1999 marked 145 years in the farming business for the Heritage family, but it also marked a new challenge. They were losing money on their peach and apple orchards, and were at risk of losing the Gloucester County farm that had been in their family for generations. Without a drastic change, the farm was on the path to bankruptcy. “We knew we had to do something that would see results in a year or two,” says Richard Heritage, director of marketing and sales and the sixth generation to work on the farm. So the Heritage family sought the advice of Rutgers Cooperative Extension. Experts there suggested that the Heritages convert the entire farm to either blueberries or wine grapes. Rich’s parents, Bill and Penny Heritage, took a risk and invested their entire life savings into converting nearly all of their 150 acres into vineyards. It worked. Just a decade after the conversion, Heritage Vineyards has continued its expansion to include not only a vineyard, but also a winemaking facility and a destination winery.

Survival stories such as these can be found throughout the area—and there are plenty of business lessons to be culled from this longevity. From West Deptford’s Henry Troemner LLC, which began in 1840 manufacturing scales and weights and now produces a variety of lab equipment, to the 125-year-old George Young Company, a machine-rigging business that’s spanned five generations, these landmark businesses have stood the test of time.

“It’s amazing to look around and see how many of these multi-generational businesses there are in Gloucester County, and they do share a lot of things in common,” says Gloucester County Freeholder Heather Simmons, liaison to the county Department of Economic Development. These secrets of success range from strong guiding principles to a readiness to adapt to changing circumstances.

We asked these stalwarts what’s enabled them to thrive—and they were glad to share insight into what has allowed them to prosper through the good times and the bad.

Lesson No. 1: Adaptability

Today’s cutting edge technology is tomorrow’s relic—which is what makes adjusting to changing times so vital. “One of those things [Gloucester County’s centenarian businesses] share is that, as time passes, these companies are able to adapt to changes in the market and technologies,” Simmons notes.

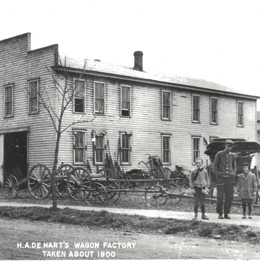

A prime example is H.A. DeHart & Son Transportation Equipment Specialists. In the early 1900s, the DeHart family saw that farm wagons, which they had been selling since 1884, were being replaced by cars and trucks. But instead of calling it quits, they chose to roll with the times and begin building truck bodies. A century later, the company is still in business, specializing in school buses, Great Dane trailers and municipal truck equipment. “We diversified; that’s the reason we’re still here,” says Dennis Noon, president of H.A. DeHart.

That same ability to take the long view and react accordingly has guided Swede’s Inn, in Swedesboro, through more than 200 years in business. Built in 1771 as a tavern along Old Kings Highway, the building served as a gathering place for many of the early patriots. A historical example of the tavern’s need to adapt was during Prohibition in the 1920s. “When Prohibition came along and they could no longer serve alcohol, they put in a car dealership,” says Toni Beltz, who now owns the business with her husband Mark. A more recent evolution came about when the Beltzes decided to add a casual dining component to a long tradition of fine dining.

“When we bought it 30 years ago, it was an old Victorian inn in the midst of total farmland, and it was very popular to go out to a country inn,” Beltz says. “Now people want things that are more casual and more happening.” Surrounding development has also given the place a more suburban feel, and they have adapted to that new aesthetic.

Lesson No. 2: Passion

Another quality that allows these family businesses to prosper is the owners’ unfailing commitment to their companies. “It’s not just their job,” says Simmons. “It’s their whole life. The children grow up surrounded by the business from dawn to dusk. And so, they’re continually surrounded with this love for the business and this drive to see the business succeed.” Richard Heritage was only 15 when his parents decided to convert the farm to vineyards, yet they came to him to request his input. “I was a sophomore in high school and my parents sat me down and they said, ‘We’re ready to take the ultimate risk, are you interested?’ I said, ‘Absolutely,’” he recalls.

Although the last member of the DeHart family exited the business in 1987, the company has kept the sense of ownership within its ranks, and is now an employee-owned company through an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP). This breeds a deep commitment to the company’s success, according to Noon.

And at Swede’s Inn, Beltz says she and her husband are constantly focused on building their business, and finding ways to improve. “You always have to be thinking. You always have to be on,” she says.

Lesson No. 3: Networking

Many of our region’s oldest companies have made themselves indispensable members of the regional business community. Beltz says that keeping in touch with both Swede’s Inn’s customers and the regional hospitality market has been the most important element of keeping their business on track. “You have to be aware of what people want and think,” she says. “We’re really ‘people’ people and adding this personal touch helps. The people know us: they know we’re the owners.”

That promise—of the same management in place decade-in and decade-out—cultivates customer loyalty that lasts through the years.

Lesson No. 4: Staying ahead of the curve

Pitman’s Campbell’s Express has been in the shipping business for 106 years. The company began as a one-buggy enterprise, company president William Messenger notes. “[The founder] was going over to the city by ferry and getting packages of supplies for the merchants in Glassboro,” he says. When the company switched over to its first truck, the name changed, too—to Campbell’s Auto Express. It was one of the very first trucks in the area, and Mr. Campbell wanted to advertise that. Later, when the company added a second truck, he painted a different number, one through four, on each side of the trucks, so that the two vehicles looked like a fleet of four.

Today, that willingness to invest in trending technology has served the company well. They’re running 70 trucks, and employing 170 workers, plus 40 employees managing 200,000 square feet of warehouse space. “We try to stay up to date with technology; we were one of the first to go to scanning for order accuracy,” Messenger says.

Likewise, the company has had to forecast its clients’ changing needs. An early major client was Sony, which began with large, heavy albums that gave way to cassette tapes, then lightweight CDs—all requiring less and less shipping volume. But long before Sony announced the closure of its Gloucester County plant, Campbell’s Express was looking to diversify its client base, adding clients in the technology, textbook and tobacco industries, among others. “Now that tobacco is declining, technology and medical supplies are increasing. So you always look at what industries are growing right now,” Messenger says.

Lesson No. 5: Hard work At Campbell’s Express, there’s a legendary story in the company about Lou Hannum Sr., one of Messenger’s forerunners. “He had a hernia operation on a Friday and was back driving on Monday, with help from his son who took a few days off of school,” Messenger says. “He had the best work ethic of anybody I’ve ever known.”

Messenger says that dedication—instilled through the generations that have owned the company and still keep a hand in it by sitting on the company’s board of directors—also attracts workers who share the same commitment. “There’s a 120 percent rate of turnover in industry, but we don't have any turnover. When workers get here, they stay here—and they retire from here,” he says. That in turn translates to customer satisfaction, since the drivers are the face of the company for many clients.

Lesson No. 6: Expertise

The founder of DeHart was a blacksmith who built the wagons himself. His deep technical knowledge gave him the confidence to continue in the changing business of transportation. Likewise, the Heritage family has six generations of farming knowledge, experience that has shaped their modern endeavors.

Simmons adds that business owners often encourage the younger generations to leave the business for a while. They often pursue higher education or work experience, and then return to the family business with new ideas and a renewed commitment to the company’s mission. Richard Heritage considered enrolling in winemaking school, but instead chose to attend Rutgers University, where he earned a business and economics degree. He says the collective wisdom of his predecessors, combined with the fresh ideas of the incoming generation, can be a potent combination. “There is extreme value in the younger generation and the older generation working together,” Heritage says. “You have me coming out of college with the theories, and then you have my parents who have lived the reality of the business. They bring reality to the marketing theory, and I give them kind of a new vision of what could be done.”

Photo: H.A. DeHart, which runs school buses for West Deptford and sells municipal truck equipment and Great Dane trailers, started out selling farm wagons.

Published (and copyrighted) in South Jersey Biz, Volume 1, Issue 3 (March, 2011).

For more info on South Jersey Biz, click here.

To subscribe to South Jersey Biz, click here.

To advertise in South Jersey Biz, click here.