It’s been a bumpy road for the long-gestating Glassboro-Camden Light Rail. But now, having navigated almost two decades of starts and stops, discussions surrounding the predominantly Gloucester County-based mass transit service have picked up steam these past few months.

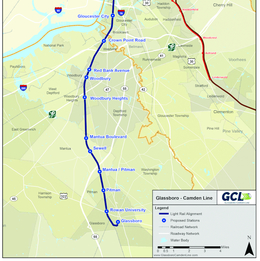

After NJ Transit commissioned a study exploring South Jersey options for mass transit in the early ’90s, the line was first put forth in 1996 as a way to connect the Glassboro area to Central and North Jersey’s transit lines, as well as those in Philadelphia, New York City and even Atlantic City. Now, the 14-stop, 18-mile line has found renewed interest again as project funding partners NJ Transit and South Jersey Transportation Authority and project sponsor Delaware River Port Authority push ahead. Advocates see its potential as everything from an asset for working commuters—especially as businesses continue relocating to Camden—that would cut down rush-hour traffic to a lifeline connecting the local economy to a brand-new and bigger audience. Christina Renna, president and CEO of Chamber of Commerce Southern New Jersey, has been with the organization on and off and in various roles since 2007, and says the rail line has been a topic of conversation throughout “the entire tenure” of her time there. The difference, however, is that this most recent resurrection of the topic has been the most promising yet. “It’s really been in the works for about 18 years,” she says. “It’s something that’s been in the queue and talked about for quite some time. … This is the first time in a very long time that we have seen true momentum that looks like it’s going to become a reality.” Part of that ongoing delay, Renna says, came from federal funds being diverted to maintaining North Jersey’s transit infrastructure instead of developing something new for the “public-transportation- deprived” South Jersey. “There are so many projects up in North Jersey that are so critical as it relates to New York City, so this line kind of got passed over throughout the years,” she explains. “There’d be some progress, but then it would go three or four years with a lull.” Renna and the rest of the chamber are excited about the prospect of mass transit coming to South Jersey. “We have been supporting and advocating for this at least for as long as I’ve been with the chamber,” she notes. “Not only are we public-transportation-deprived, but generally speaking, any kind of mass-transit options we can get in South Jersey will increase the mobility of residents and increase the functionality and attractiveness of different towns.” Renna and the chamber aren’t the only ones looking forward to the line. Wenonah resident Larry DiVietro owns Land Dimensions Engineering, a Glassboro-based firm specializing in land use and design, and sees the project as a vital link that will help the region, both locally and beyond. “I think it is very, very much needed to keep South Jersey competitive with the rest of the state, both in its quality of life and as well as a notion of economic development,” he says. “To me, it creates a ‘walkable community,’ where you can live in that suburban environment with a more cost-effective, better quality of life than you’d find in a more urban setting, but still have access to all these local amenities.” The rail line would travel between a terminal in Glassboro and the hub at Camden’s Walter Rand Transportation Center, with stations at Rowan University, Pitman, Sewell, Woodbury and Gloucester City, to name a few. Renna describes its “eds and meds corridor” connections as particularly beneficial to students at Rowan University’s main location in Glassboro and both Rowan’s and Rutgers’ Camden campuses, as well as those individuals either working or seeking treatments at hospital systems like Inspira, Cooper and Virtua. For those reasons and more, Rowan University officials welcome the project. “We are very excited about the proposed rail line, as are the students,” says Joe Cardona, Rowan’s vice president of university relations. “Our Student Government Association, in fact, just passed a resolution in support of it.” It’s a project that Senate President Stephen Sweeney has long pushed for, vocally vowing to use his position to further the project. “I’m not going to be sitting at the table and not advocating for something that’s important to the region,” he said at a DRPA board meeting nearly a decade ago. “We have very little mass transportation in this region of the state.” Not everyone is thrilled with the project. Some of that pushback comes from those who are wary of Sweeney’s motives, from unanswered questions to suspicions over his leadership role in the The International Association of Bridge, Structural, Ornamental and Reinforcing Iron Workers Union. Residents who live along the proposed route fear disruptions to their daily lives, construction and operation of a rail line impacting the local environment, the noise pollution of a running rail line and an adverse effect on local towns’ identities. In 2014, the township of Wenonhah shot down a proposed station with 514 votes against and 371 in favor, while newly formed organizations like Say No to GCL take issue with the already-dated technology of a rail line nearly 20 years in the making bringing inefficient transportation infrastructure to the region. Say No to GCL, like many individual residents, feels that money could benefit their communities in better ways—and ones they have a say in. But DiVietro sees it from another point of view. “Obviously, people who live along the route don’t want trains coming through, and there will be an impact,” he says. “But at the same time, looking into the future, change is good, and the benefits are environmental, they’re in the quality of life, affordable housing and economic development. They all outweigh the negatives.” The environmental impact has been a significant concern throughout the duration of the project. Renna describes it as being “a sticking point for a while,” with funding once again being an issue in terms of making those studies possible and public hearings needing to run their prescribed courses. With that aspect finally wrapping up earlier this year, the next phase is the rail line’s preliminary engineering and design. The timing is accidentally auspicious. More than a year of pandemic life has ushered in a local real estate market unlike any other, with longtime New York City and northern New Jersey residents eager to leave the claustrophobic and expensive city life for South Jersey’s comparatively lower costs of living and more wide-open spaces. As that northern exodus floods the South Jersey market with new residents making Burlington, Camden and Gloucester counties their homes, she sees the Glassboro-Camden line as a way to uncover some of the region’s best-kept secrets. “Those 14 stations are going to link to some of the communities, especially in Gloucester County, that are really, really growing,” says Renna. “It’s going to make that whole corridor a more attractive place to work and live, and open people’s eyes to places they’ve never heard of.”

Click here to subscribe to the free digital editions of South Jersey Biz.

To read the digital edition of South Jersey Biz, click here.

Published (and copyrighted) in South Jersey Biz, Volume 11, Issue 4 (April 2021).

For more info on South Jersey Biz, click here.

To subscribe to South Jersey Biz, click here.

To advertise in South Jersey Biz, click here.